Discover insights, tips, and stories from the skies — from aircraft buying guides to pilot training.

Published: October 16, 2025

Landing an airplane on land is already a precise task, but doing it on water adds an entirely different level of difficulty. While it might look calm from above, the surface of the water hides unpredictable challenges that can turn a controlled descent into a life-threatening situation. Understanding why landing in water is risky helps explain why pilots train so carefully for these rare events—and why survival rates vary so widely depending on conditions.

When you think of a water landing, the famous “Miracle on the Hudson River” might come to mind. That event showed how skilled flight crews can make an emergency landing on a body of water and save lives. Still, it’s important to know that water landings are among the hardest maneuvers in aviation because so many factors must go right at once. Let’s look at what makes landing on water so dangerous—and how pilots prepare for the worst.

When an aircraft tries to land on water, the biggest issue is control. The surface of the water constantly changes due to waves, wind, and visibility. Unlike a runway, water doesn’t provide a solid or predictable surface for braking or stability. The height above the water can also be hard to judge, especially over glassy water, where reflection makes it seem deeper or smoother than it really is.

During a ditch or emergency water landing, the pilot must slow the airplane enough to prevent it from digging into the water or flipping over. Even with a controlled descent, hitting the water too fast or at the wrong angle can tear the fuselage, break the landing gear, or cause a sinking airplane within seconds.

Some key dangers include:

Famous ditching incidents show how unpredictable it can be. In Airways Flight 1549, all passengers survived because of ideal water conditions and quick action by the flight crews. However, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961, Air Niugini Flight, and Flight 923 show how bad waves, fuel loss, or poor coordination can lower survival odds dramatically.

In general aviation, most emergency landings on water end with passengers and crew needing to evacuate quickly using survival equipment like life vests, a life raft, or other emergency equipment. The NTSB and aviation safety network report that many aircraft landing attempts on water fail due to the airplane flipping or breaking apart before everyone can get out of the airplane.

The risk increases in deep water where rescue takes longer and water conditions shift fast. Even advances in aviation haven’t removed this danger—because water itself is unpredictable.

| Techniques | Purpose | Example/Application |

| Controlled descent | Slows the aircraft before impact | Used in emergency water landing procedures |

| Landing parallel to waves | Reduces water resistance | Prevents flipping during touchdown |

| Use of flaps and gear | Adjusts lift and drag | Keeps landing gear retracted unless advised |

| Cabin preparation | Ensures passengers are ready | Includes life vest briefing and seatbelt checks |

| Communication | Guides rescue operations | Coordinates with aviation safety teams or ATC |

| Evacuation drills | Increases survival rates | Helps passengers and crew exit fast |

| Selecting landing area | Avoids rough or shallow water | Aims for calmer water surface conditions |

During a forced landing, pilots are trained to prepare for a water landing by picking a body of water with minimal waves, such as a river, bay, or lake. If they must ditch in the Atlantic or landing near an open sea, they plan a controlled descent parallel to the swells to soften impact.

The pilot also calculates fuel levels, height above the water, and airspeed to ensure a safe landing. Commercial airliners follow strict aviation safety procedures, including turning off engines, sealing the fuselage, and having flight crews ready with life rafts and survival equipment.

Some aircraft like flying boats or seaplanes are designed to land on the water and float afterward. But in commercial flights, any aircraft on the water is considered in an emergency landing scenario.

Before impact, flight crews secure the cabin and tell passengers and crew members to brace. After touching the water surface, their goal is to evacuate onto life rafts before the airplane in the water sinks. The NTSB data shows that survival rates vary depending on training, coordination, and water conditions.

Even with advances in aviation, general aviation pilots still practice ditching the airplane during training. They learn to land in a river, make an emergency water landing, and avoid hitting the water nose-first. The focus is always on giving the passengers and crew aboard the best survival odds possible.

While runway landings are always the intended goal, being ready to land on water can mean the difference between tragedy and another miracle on the Hudson.

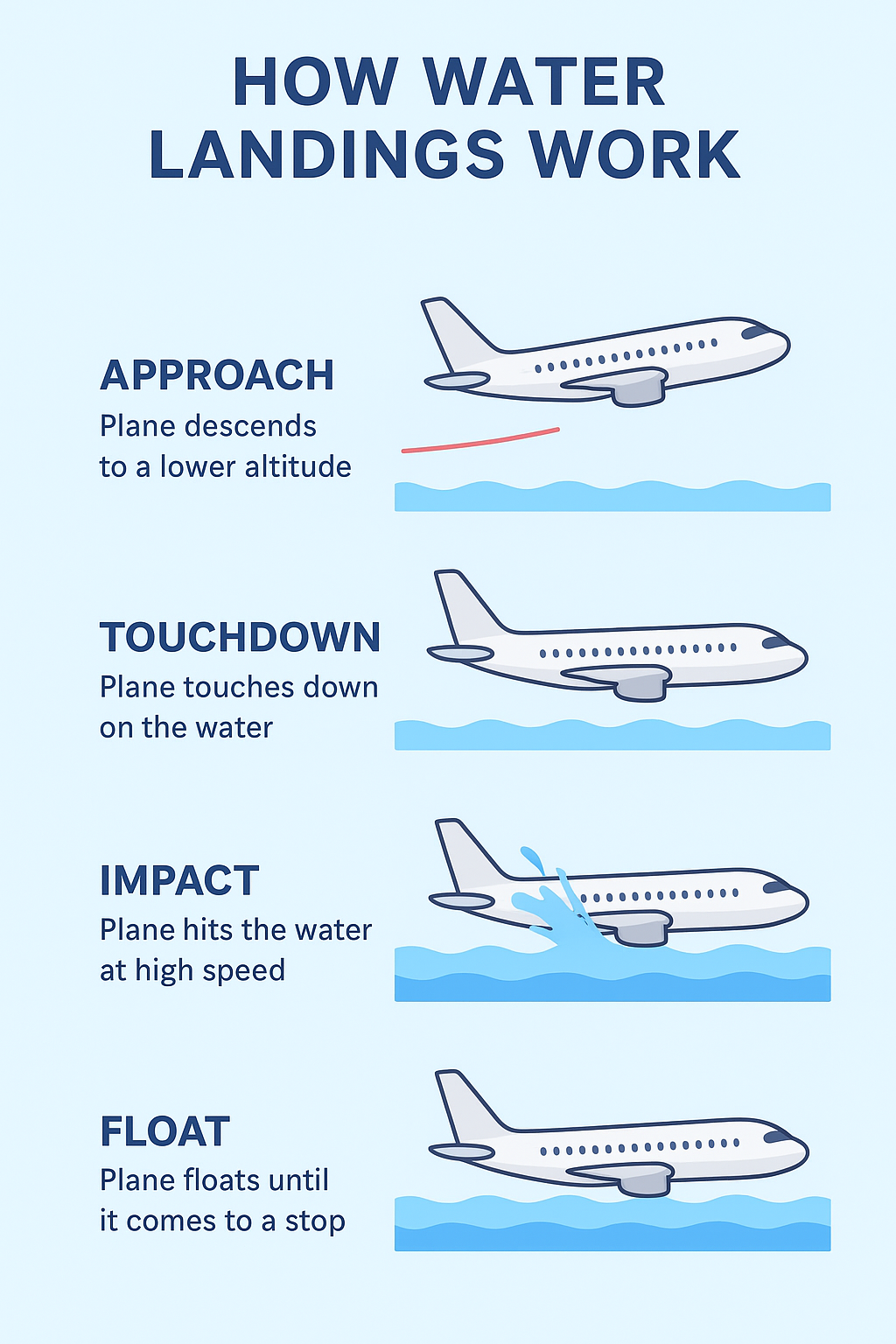

When an airplane makes contact with water, the process looks calm from a distance—but it’s far from simple. Every second counts, and every movement the pilot makes is carefully planned to control how the aircraft hits the surface. To understand how water landings happen, it helps to look at each stage and what the crew does to keep everyone safe.

Before touching the water, pilots prepare the aircraft and passengers for impact. The intended landing might have been at an airport, but an emergency changes everything. Pilots must quickly choose the safest body of water available—calm, open, and free of obstacles.

They slow the plane and line it up parallel to the waves. This position helps the aircraft skim across the surface instead of slamming into it. Pilots usually:

Communication is constant during this stage. The pilot tells air traffic control the position and situation. The flight crews move passengers into brace positions and ensure everyone has life vests ready. The goal is to prepare for the safest possible impact while keeping panic low.

As the plane nears the surface of the water, the pilot gently raises the nose. This move slows the descent and spreads the force evenly across the fuselage. A perfect entry angle can make the difference between a successful water landing and a serious accident.

But even perfect handling can’t change one fact—water is more likely to cause unpredictable results than solid ground. The surface moves, the waves shift, and light reflection can make it hard to judge exact distance. This is one reason water landings so dangerous in the first place.

When the plane touches down, it skips, slides, and eventually slows down as drag increases. The key is to avoid digging the nose into the water. If that happens, the aircraft can flip or break apart. Pilots often describe this part as the hardest few seconds of their careers.

For example, in 1963, a Pan Am flight ditched in the North Atlantic after multiple engine failures. The crew’s calm coordination allowed many passengers to survive. They kept the aircraft steady and landed parallel to the waves, proving how preparation and teamwork can save lives even in freezing water.

Once the aircraft comes to a stop, it might float for several minutes or even longer. How long depends on design and damage. Sealed sections of the fuselage can trap air and keep the aircraft from sinking immediately. Still, the goal is always to evacuate fast.

Pilots and crew lead passengers toward emergency exits. Slides often turn into life rafts, and everyone must stay together for rescue. The closer the landing is to the coast or flight path, the better the rescue odds.

Aircraft designed for landing on land are not meant to float forever. That’s why most procedures focus on getting everyone out quickly, not keeping the plane above water. Even small leaks can cause the aircraft to sink within minutes, especially in rough seas.

In aviation, success means everyone survives—and the odds depend on dozens of details. While pilots train for water emergencies, conditions rarely cooperate. The intended landing might be smooth in a simulator, but real life brings rain, waves, and unpredictable winds.

On a runway, pilots know exactly what they’re dealing with. The surface doesn’t move. Distance and height are clear. Even in heavy rain, the landing gear and brakes help stop the plane safely.

But on water, things get complicated. Here’s why:

Even though pilots follow strict training, water landings so dangerous because one wrong angle or speed can destroy the fuselage instantly.

Some events in history highlight how complicated these situations can be. The Miracle on the Hudson is one of the most famous modern examples. The pilot had only minutes to react after both engines failed, yet he managed to glide the aircraft across the Hudson River perfectly. All passengers survived.

In contrast, other flights haven’t been so fortunate. Many smaller aircraft, including general aviation planes and seaplanes, have faced problems judging the height above the water. Even when pilots perform well, rough conditions can turn a controlled ditching into a dangerous slide or spin.

For larger commercial airliners, every decision must be perfect. In 1963, when the Pan Am flight ditched in the North Atlantic, rescue teams had to act fast before cold water overwhelmed survivors. The lesson from that day remains clear: even the most skilled crews can’t control nature.

Modern aviation has improved through lessons learned from past emergencies. Pilots now practice emergency procedures in simulators that mimic real waves, light conditions, and crosswinds. Every maneuver helps build muscle memory for those rare moments when a pilot must land on a runway—or water.

Pilots are trained to:

Even though a successful water landing can save lives, pilots are always taught to prioritize landing on land when possible. That’s because a solid surface allows better rescue access, less damage, and higher survival rates.

New aircraft designs focus on structural integrity and float time. Some have stronger fuselages, improved buoyancy compartments, and waterproof materials. Communication systems now alert rescue teams instantly, improving response time.

Still, even with all this progress, water is more likely to pose life-threatening risks than solid ground. A successful water landing remains the exception, not the rule.

After the aircraft stops, everyone’s attention shifts to survival. Evacuation starts immediately. Passengers and crew work together to deploy life rafts, grab emergency supplies, and stay clear of debris.

Those who remain calm usually have the best chances. Even though it can be hard to think clearly after impact, following the crew’s instructions makes all the difference.

Water temperature, time of day, and distance from land all affect rescue outcomes. For instance, when the Pan Am flight ditched in the North Atlantic, freezing conditions made survival extremely difficult. But the quick response of rescue ships saved dozens of lives.

The main goal after landing in the water is to stay afloat and visible until help arrives.

Water landings demand precision, patience, and courage. Pilots do everything possible to keep control during emergency landings, but unpredictable conditions often define the outcome. On calm seas, a successful water landing is possible. In rough weather, even the best efforts can end differently.

Although modern technology and training improve survival odds, pilots and passengers alike still hope for one thing—to land on a runway every single time. Because in aviation, a safe landing is always the goal, and water should remain the very last option.

Landing an airplane on water may sound peaceful, but in reality, it’s one of the most dangerous things a pilot can face. Between unpredictable water conditions, aircraft design limits, and quick survival decisions, success depends on skill, timing, and training. Each water ditching reminds us how vital aviation safety standards are for protecting lives.

If you want to learn more about why landing on water is dangerous, or explore more insights into aircraft performance and aviation safety, visit Flying411.com for expert guides, flight stories, and aviation updates.

The main danger is loss of control due to unpredictable wave patterns, which can cause the airplane to flip or break apart during impact.

Pilots train to land parallel to waves, slow their descent, and prepare passengers for evacuation using life vests and rafts.

Aircraft with sealed fuselages or lighter materials can stay afloat longer, giving passengers more time to evacuate.

Key factors include temperature, wave height, rescue speed, and how well passengers follow evacuation instructions.

They are extremely rare thanks to better aircraft maintenance, navigation systems, and stricter aviation safety regulations.