Discover insights, tips, and stories from the skies — from aircraft buying guides to pilot training.

Published: October 17, 2025

Float planes have always captured attention for their ability to land on water and take flight again with ease. They bridge two worlds—sky and sea—bringing access to remote areas that no runway could ever reach. From scenic tours to life-saving missions, float planes have become essential in the aviation industry for their flexibility and dependability.

But what makes a floatplane different from other aircraft? And how does it manage to take off from water while carrying passengers, fuel, and gear? This post goes over what these unique aircraft designed for water operations can really do.

At its core, a float plane is an aircraft equipped with special pontoons, or floats, that let it take off and land on water. These floats replace the standard landing gear you’d find on land-based aircraft, allowing the plane to safely operate in lakes, rivers, or coastal areas.

Here’s a simple breakdown of how they work:

| Component | Function |

| Floats (Pontoons) | Provide buoyancy so the plane can rest on water. They keep water from entering the fuselage. |

| Hull or Fuselage | In some designs, the fuselage itself acts as a boat hull—like in a flying boat. |

| Propeller and Engine | Generate thrust to move the aircraft forward for takeoff and flight. Many use Lycoming or turboprop engines. |

| Flaps | Help increase lift at low speeds, crucial during take-off and landing from water. |

| Amphibious Floats | On an amphibious aircraft, these floats include retractable landing gear, allowing it to operate on both water and land. |

Float planes fall into two major categories:

A seaplane pilot typically flies using visual references, especially when judging water conditions for takeoff. Since water doesn’t offer a fixed surface like a runway, the pilot checks waves, wind direction, and obstacles before attempting to alight or take off from water.

Many floatplanes and flying boats use single-engine or twin float setups. A good example is the DHC-6 Twin Otter, known for its STOL (short takeoff and landing) ability, which makes it perfect for tight spaces and remote zones.

The first seaplane took flight in the early 1900s, leading to aircraft like the Supermarine racers built for the Schneider Trophy and wartime models such as the Short Sunderland and Consolidated PBY Catalina used during the First World War and end of World War II. Even the Italian Navy and German aircraft makers developed early commercial flying boat designs for transatlantic flight.

Today, modern floatplanes like the ICON A5 and Cessna Caravan are popular for recreational flying and general aviation missions. Some even feature retractable landing gear, advanced fuel tanks, and corrosion-resistant materials to reduce water from the floats and extend lifespan.

From bush flying in Alaska to tourist flights across island nations, these utility aircraft show how unique capabilities in design make the ability to land on water possible—safely, reliably, and efficiently.

Float planes play a big role in the aviation world because they make travel possible in areas with no runway or airport. Think of a bush plane landing beside a mountain lake or a Cessna carrying supplies to a fishing village deep in the wilderness.

Here are some reasons why they’re essential:

Floatplanes serve regions without developed infrastructure. They connect small communities, deliver goods, and support medical evacuations. In many parts of Canada, Alaska, and the Pacific Islands, they are lifelines for survival.

Many scenic tours use seaplanes like the Cessna Caravan or Twin Otter to show travelers beautiful landscapes. Seaplane pilots also undergo special FAA certification to safely perform water operations, understanding factors like wind, wave patterns, and buoyancy.

During wartime, models like the Kingfisher and Short Sunderland operated as patrol and rescue aircraft. The Boing and Supermarine companies produced flying boats that could land on the water during missions. In modern times, amphibian and amphibious aircraft continue to assist in firefighting, surveillance, and rescue operations.

Modern floatplanes are part of general aviation, used by both private owners and businesses. They’re adaptable—some feature pusher propellers or retractable designs that switch between land and water use. The de Havilland Beaver and Cessna 206 are famous examples known for their reliability and long-range performance.

Over time, the aviation industry improved materials to reduce corrosion, improve fuel efficiency, and manage larger and heavier payloads. The IO-540 engine, used in many single engine seaplanes, provides strong thrust for quick take-off and landing in limited space.

The development of floatplanes during the First World War helped shape aircraft design standards we see today. Early landplane models were adapted for sea use, giving rise to hybrid designs that could land-based or land on the water depending on mission needs. Some of these historic aircraft can still be seen at the Imperial War Museum.

Float planes represent freedom in the aviation world—the ability to explore places others can’t. Their mix of strength, balance, and reliability makes them valuable even today, as new aircraft continue to borrow from their unique capabilities.

Operating a floatplane may sound like a simple idea—attach floats to a plane and let it take off from water—but there’s much more happening beneath the surface. From how it moves before takeoff to the way it lifts off the water, every step relies on careful control, design, and understanding of physics.

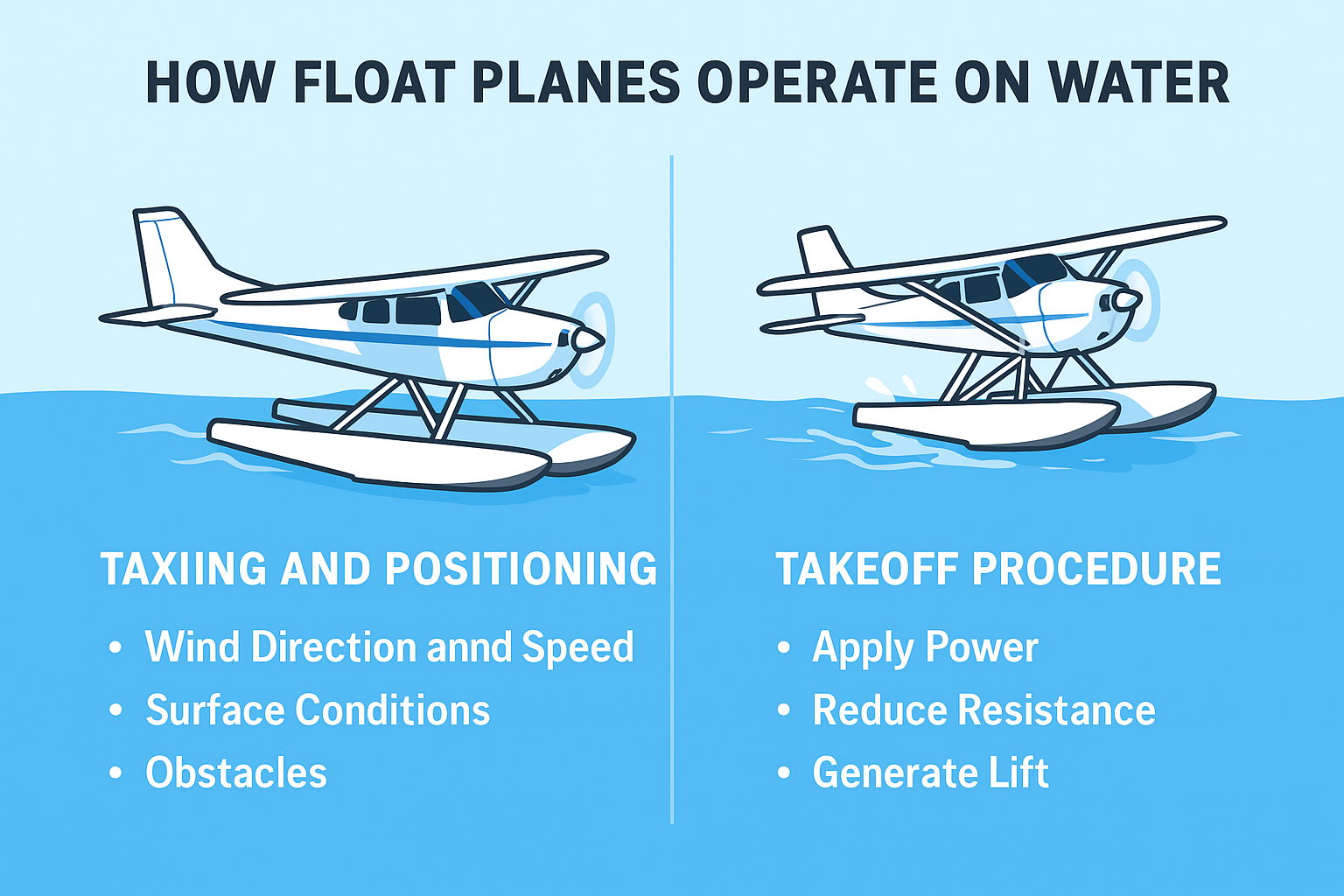

Before any aircraft on the water begins its operation, pilots must evaluate their surroundings. Unlike a typical land plane, a float plane doesn’t have a paved runway or taxiway. The water itself becomes both the runway and the landing zone.

Here’s what pilots usually check before taking off:

Water operations depend heavily on pilot experience. Conditions change constantly, and a good seaplane pilot learns to read the water before every flight.

Once the pilot starts the engine, the plane begins to move slowly across the water in what’s called a taxi. This stage is similar to ground taxiing in traditional aircraft but with a few key differences.

Since there are no solid brakes or wheels, float planes steer using rudders on the back of their floats. Some even use a water rudder system that helps maintain direction at low speeds. Pilots use gentle power adjustments to stay steady, especially in windy or choppy conditions.

Here’s what happens step-by-step:

Good water handling is key to a smooth departure. Poor technique can cause the floats to bounce or “porpoise,” which can be dangerous if not corrected quickly.

A float plane’s takeoff from water looks simple from a distance, but it involves careful balance and timing. Pilots apply power gradually, allowing the floats to rise onto what’s known as “the step.” This position keeps most of the floats above the water, reducing resistance.

Here’s how it works:

Because water creates more drag than a runway, float planes need a longer takeoff distance than typical land-based models. Pilots use flaps to generate more lift, helping the aircraft designed for water rise faster.

Float planes like the Cessna Caravan or the DHC-6 Twin Otter are popular because their engines produce enough power for short take-off and landing operations. Even so, pilots always factor in wind, temperature, and water density when planning their takeoff run.

Once in the air, a float plane behaves like other aircraft in many ways. It follows the same aerodynamic principles and responds to similar flight controls—aileron, rudder, and elevator. However, there are a few things that make it unique.

Key Flight Differences

Many floatplanes rely on rugged construction and powerful engines to offset the extra drag. Aircraft such as the de Havilland Beaver and Cessna 206 use Lycoming or turboprop engines, known for their strength and reliability in tough environments.

Landing on water requires precision and patience. A pilot must carefully balance speed, pitch, and power to avoid bouncing or skipping across the surface.

Here’s how a typical landing goes:

Pilots also plan for what happens after landing. For example, they may need to taxi toward a dock, anchor, or shoreline depending on the mission. Because water doesn’t offer grip, float planes often drift, so precision control is vital.

A big reason float planes perform so well lies in their engineering. Aircraft manufacturers design them to handle unique stresses, such as waves, spray, and corrosion.

Here are some standout aircraft features that make them ideal for water use:

Manufacturers like Boeing and de Havilland have contributed greatly to these innovations. Over time, lessons from military and commercial flying boat operations improved safety and performance for modern float planes.

The concept of float planes goes back to the early 1900s, with the aircraft of the first water landings inspiring a new chapter in flight history. Pioneers like Henri Fabre, who built the first seaplane, showed how floats could replace wheels entirely.

Soon after, major companies like Boeing began experimenting with monoplane and biplane configurations capable of water takeoffs. These innovations paved the way for flying boats and amphibious designs used during global exploration and wartime operations.

Some of the earliest designs were adapted from land plane models, showing how creative engineers could be. Instead of a standard undercarriage, they attached pontoons or designed a hull-shaped fuselage. By the end of World War, advancements in floatplanes led to faster speeds, longer ranges, and improved safety features.

Historical models like the Short Sunderland, Supermarine, and Consolidated PBY Catalina became icons for their range and reliability. Even today, their influence is seen in modern seaplane designs that combine classic durability with modern avionics.

Operating in water means constant attention to safety and care. Corrosion, floating debris, and wave impact all pose risks. Regular maintenance is crucial to keep the aircraft seaworthy and flight-ready.

Pilots and mechanics typically inspect:

Float planes that undergo regular checks stay more reliable and last longer, even under harsh conditions. The FAA provides detailed inspection guidelines for seaplane operations to ensure they meet aviation industry standards.

Float planes stand as a special kind of aircraft designed for freedom and adaptability. They handle like agile boats on the surface and graceful planes in the air. From early pioneers to modern designs, these utility aircraft continue to expand the limits of where people can travel.

Their evolution—from experimental monoplane prototypes to dependable amphibious models—shows how innovation keeps aviation exciting. With strong floats, smart engineering, and skilled pilots, float planes connect people to places few others can reach.

No matter how advanced technology becomes, the sight of a float plane lifting from a quiet lake or gently touching down on open water remains one of the most captivating scenes in all of aviation.

Float planes remind us how creative design can make flying possible anywhere—on lakes, rivers, or open seas. From the first seaplane to today’s advanced amphibious aircraft, they’ve shown what versatility truly means.

If you’re curious to learn more or want to find new aircraft for sale, visit Flying411.com to explore guides, listings, and expert insights about different types of float planes and other aircraft in modern aviation.

Most float planes cruise between 120–160 mph, depending on their engine type and size.

Only amphibious models with wheels or retractable landing gear can safely operate on both water and land.

A float plane uses pontoons under the fuselage, while a flying boat has a boat-shaped hull that sits directly on the water.

Yes. Pilots need a seaplane rating from the FAA to operate float or amphibious aircraft safely.

They can stay afloat for extended periods, but maintenance checks help prevent corrosion and ensure the floats stay watertight.